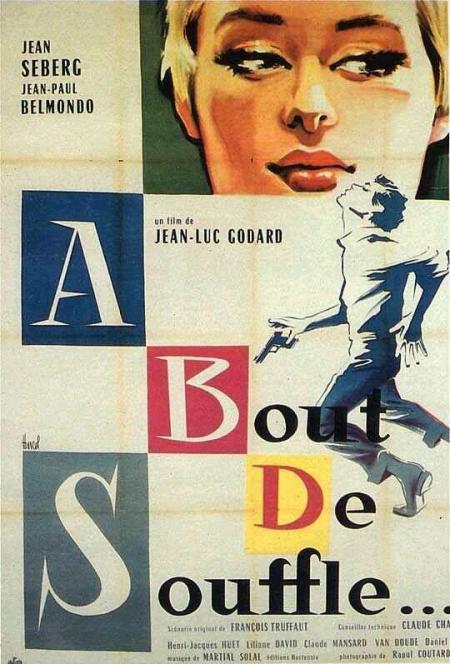

This arrival of The Girl on a Motorcycle from LoveFilm couldn’t have been neater. Consider that it is directed by Jack Cardiff, the genius cinematographer from Black Narcissus, who I have discussed in some depth recently, featuring Marianne Faithful (I’ve already discussed Anita Pallenberg the other infamous Stone-ette this week) and Nouvelle Vague icon Alain Delon ahead of my planned weekend of film Francophilia. How neat a bundle of coincidences could I want?

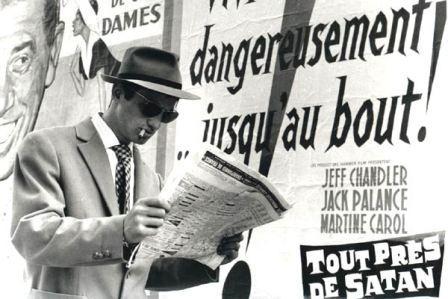

Jack Cardiff directs Alain Delon

Against that backdrop, though, the film could surely only disappoint. And it sadly does.

Often I will reflect that the more innovative and distinctive a film is, the more likely it is to be referenced, to influence and to be stolen from. And by that process the elements which inspire admiration- perhaps even adoration- come to seem mundane and commonplace. For the film fan trawling through the past, it is hard to fully appreciate the context in which a film was first seen. Coming just twenty years after the end of the second World War this film features Marianne Faithful passing a soldiers’ graveyard and questioning the validity of the war and the sacrifices made- was this shocking iconoclasm or were many contemporaneous films exploring the same rueful territory?

I mention this because this film features extensive use of acid-coloured solarization, so much so that Jack Cardiff begins to irritate as if he were a child with a toy drumkit. Of course, the process also allows him to get away with longer and more graphic sequences of Faithful and Delon romping than would probably have been allowed otherwise. But I couldn’t help thinking to myself “what’s the point of going to all that trouble to show something that the viewer can’t recognise anyway?”. Whether these ‘groovy’ scenes achieved their aim in the 60s or not, I can’t confirm- but they date the movie badly now and look clumsy and ineffective now.

And The Girl on a Motorcycle is really summed up by that. It is a film of worthy- though frankly ill-judged- intentions, attempting to record on film the thought and ambitions and streams of consciousness of a girl riding across continental Europe. Like a rites of passage road movie with one protagonist. Judged against such ambitious aims, it fails mightily. In fact, it is of no more merit than any number of cheap 60s exploitation B-movies. The plotline- the bit that isn’t summed up by the title anyway- is told largely in flashback. Marianne Faithful’s character Rebecca leaves her staid husband of a couple of weeks, the failing teacher Raymond (Roger Mutton- terrible actor but the wearer of a great quiff!) for Alain Delon’s character Daniel, who she met and commenced an affair with in the run-up to the Wedding. Daniel is the only character in the piece of any substance whatsoever- maybe because Delon and Powell and Pressburger stalwart Marius Goring in a very minor role are the only actors of any merit on show. He is callous, manipulative and egotistical; though we discover that this bravado masks the deep pain of heartbreak.

The dialogue- which is mainly concerned with expressing Rebecca’s inner thoughts and feelings- is stilted, obvious and typically vacuous Haight-Ashbury hippy nonsense- “not everyone who is dead has been buried”; “sometimes it’s an instinct to fly. I’m not going to feel guilty”; “Rebellion’s the only thing that keeps you alive”- that kind of bollocks. And only Delon’s character- somewhat implausibly a university lecturer- has any lines which steer clear of cliché – during a seminar on, believe it or not, the morality of free love he opines “love without love, desire without love…so what is love? … A blanket to cover all the dark emotions- desire, lust, a need to hurt, to be hurt”. This isn’t to say he escapes the scriptwriter’s clunking prose throughout- his “Your body is like a violin in a velvet case” may well worst first line for any movie character ever.

It is all so disappointing given the calibre of the people involved. There are blatant continuity errors, logical gaps (Daniel must be supernatural as he appears in a locked room at one point without any explanation how), wooden performances and lowest-common-denominator innuendo with the motorbike as a big cock. The Girl on a Motorcycle features a girl on a motorcycle on a low-loader- did no-one think that the lean and steering involved in cornering would make Faithful sat bolt upright as the bike takes a hairpin look pretty bloody stupid? Oh I despair! A French film by an English Director shot in Switzerland with the Frenchman Alain Delon as a German and the English Marianne Faithfull as a Swiss. This is all too much to bear.

I’m not generally in favour of remakes (not least because they keep that goofy slapheaded tit Nic Cage in work) but there is the kernel of a good idea in here being woefully badly executed. This could have been an exploration of freedom, of the feminist movement, of the futility of free love, of the futility of marriage, of existentialism, of expressionism, of any message the film-maker wants to say. The premise is a blank canvas. It could have been an artistic exploration; it could have been a beautifully simple road movie; it could have been any number of worthy and interesting things. But what it is, I’m afraid, is a fucking mess. If any film ever required a remake, this is it.

Devoid of subtlety, intrigue, wit or beauty, this is a very poor exploitation film. The only bit I liked at all was the sequence where Faithfull composed her farewell letters in a café, whilst Jack Cardiff filled the screen with faces of old men. It said nothing of interest, I just thought it looked nice. Oh, and I also liked the following exchange: “Love is a feeling” “so is toothache”. 2/10

Posted by Vern McIlhenney

Posted by Vern McIlhenney